The program is on the edge for continued support from the UCLA Athletic Department and Zenon Babraj is hired as a full-time coach.

Excellence and the National Collegiate Rowing Championship

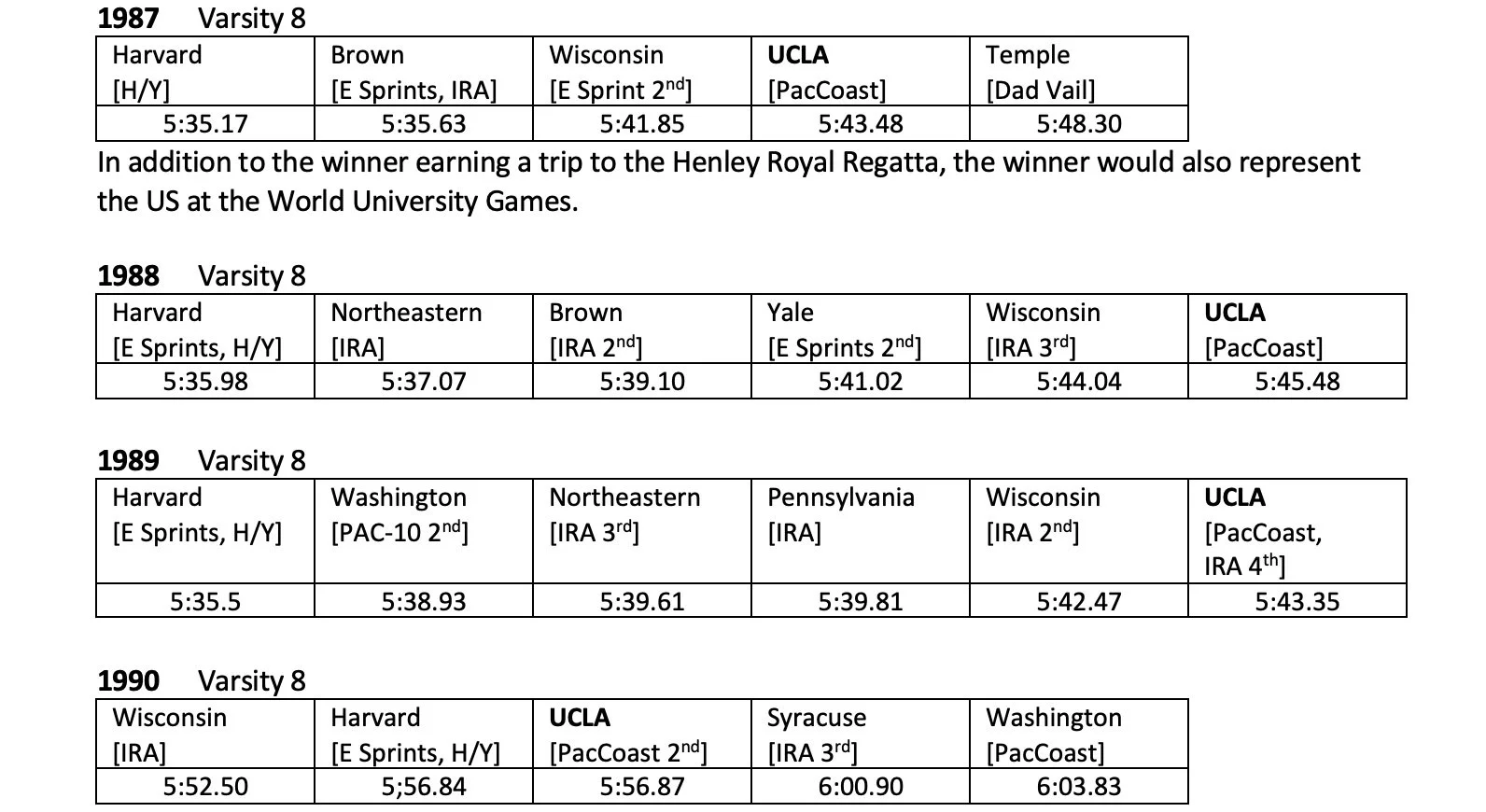

1987 - 1991

|

1987 - 1991 |

In the previous year, the Athletic Department had reduced the men’s coach to a part-time position and instituted a program evaluation process, the precursor to dropping the sport. The work by a small group of alumni worked to increase the awareness and appreciation of the program and to fund raise for a $3 million endowment financing the men’s heavyweight and lightweight programs and the women’s program. The 1986 UCLA Classic indeed generated excitement. Shortly after the Classic, athletic director Peter Dalis stated that the University was willing to make a three-year commitment to supporting the sport of rowing at the same level as 1986 ($75,000) and if F.O.U.R. desired full-time coaches they would need to fund a portion of the annual operating budget. This required F.O.U.R. to commit to raising $40,000 for 1986-1989 toward the operating budget in addition to its endowment goal which was now going to be within the UCLA Foundation. The initial $40,000 for 1986/87 was raised in a five week period, and thus allowed UCLA to hire Zenon Babraj as a full-time coach. Craig Bleeker, “President’s Report”, Bruin Strokewatch, September 1986, 1-2. and Terry Oftedal, “F.O.U.R. succeeds in Fund Raising Role”, Bruin Strokewatch, September 1986, 2.

Zenon Babraj, UCLA Head Coach

Zenon Babraj (pronounced Bob-rye) defected from Poland in 1984 where he had already been successful at rowing both as a member of the Polish national team (1969-1978) and a coach preparing national level athletes. Wherever he went as a collegiate coach in the United States, success came with him. His first stop in the United States was as a volunteer assistant coach at Washington under Husky head coach Dick Erickson for one season, though he had initially planned to work on a fishing boat in Alaska. He was the head coach at the University of Cincinnati in the spring of 1985 and directed the Cincinnati Rowing Club. During the 1986 season he was freshman and assistant coach at Brown. In addition to Brown’s varsity eight winning the IRA in 1986, so did Babraj’s freshman in the eight and four-with-coxswain. In the summer of 1986, he was an assistant coach to U.S. national team coach Kris Korzenowski. Babraj came highly recommended by Brown’s coach Gladstone and Korzenowski. “New Era Dawns on UCLA Rowing Program”, Bruin Strokewatch, September 1986, 1.

In a 1989 newspaper article, Babraj’s no nonsense, lead-by-example coaching style was described by his freshman coach Lee Miller, “He turned everything upside down. It was ‘my way or the highway.’ He started by throwing people off the team. Then he had to teach people to row. Then he had to teach the proper mental attitude.” It was described that, “he has thrown problem rowers out of the boat and climbed in himself, coaching from the offender’s seat.” Tina Fisher Forde, “A Warsaw Concerto”, Los Angeles Times, 12 Apr 1989, III-1.

Babraj led the program at UCLA for five years, until 1991 when the program lost varsity status. In his first year at UCLA the Bruins earned their first of three consecutive Pacific Coast Championships, followed by two Pacific Coast runner ups, with trips to the National Collegiate Championship during each of those years including a third place finish in 1990. There was also an entry in the Grand Challenge Cup at the Henley Royal Regatta in 1988 and three finalist varsity crews at the 1989 IRA. While at UCLA, he produced seven National Team athletes and three Olympians. In 1987, Zenon was an assistant coach for the U.S. at the World Championships in Copenhagen, Denmark, helping lead the eights to a gold medal. In 1989 he served as head coach for the World University Games held in Duisburg, Germany. USC women’s rowing coaches: Zenon Babraj, web usctrojans.com/sports.

After his time at UCLA Zenon and Kelly Babraj moved to Alaska and opened the Alaska Sports Academy, training individuals and teams in several sports at the high school, collegiate, and elite level. Together they coached a number of athletes who went on to compete on U.S. National teams in their respective sports. The pair left Alaska in 1999 when Zenon was again hired as an assistant rowing coach with the U.S. National Team in preparation for the World Championships. Zenon turned down a permanent position with the National Team in 2000 to instead rebuild a struggling program at Hobart College in Geneva, N.Y. At the same time, Kelly accepted the head coaching position at William Smith College (Hobart, a men’s private college, is a brother school to William Smith, a women’s private college), where the pair spent three years (1999/2000-2002). Zenon led the Statesmen to two undefeated seasons (2001-02) and his crews finished as the top Division III team at the 2002 Head of the Charles. USC women’s rowing coaches: Zenon Babraj, web usctrojans.com/sports.

Zenon Babraj served as USC’s women's rowing head coach and director of rowing for 15 seasons (2002/03 through 2016/17, the first six years as co-head coach with his wife, Kelly) before resigning. USC athletic director Lynn Swann stated that “Under his guidance, USC women's rowing became a nationally-prominent and nationally-competitive program,” including ten NCAA championship berths and fourth place finish in 2013. “Zenon Babraj Resigns as USC Women’s Rowing Head Coach/Director of Rowing”, 17 May 2017, web usctrojans.com/news.

Zenon passed away in May 2025. His passing was highlighted in the Summer 2025 Strokewatch:

What hasn't been said yet is how strongly valued Zenon was by his athletes. This was the case for a variety of reasons. His confidence, and albeit, his courage led to many great qualities including his openness and ability to be accessible to our questions, and then giving us honest and fair answers in return. Another great quality of his, as a coach, was that he ran a very fair and professional process for selecting people for the first boat and second boats through seat racing.

First, Zenon was very professional, precise, and fair when racing the boats. Second, you never knew how many pieces you were going to race, or who was going to be switched, so everyone was on notice that they could be switched and raced next. Basically, anytime anyone was being raced everyone else was on notice that they could be next. This made sure everyone was pulling their hardest all the time.

Essentially, he created a high functioning meritocracy, which bred a spirit of hope and possibility in the crew which ultimately led to performances that charted new achievements for his crews. In 1987, at UCLA the team went from 4th in the Pac-10 to 4th in the Nation and the first PAC-10 championship in 17 years. Under Zenon an otherwise dismissed nerd could make the first boat if they could make the boat move. By rewarding performance and removing the element of a social hierarchy and popularity from the selection process, he created a spirit of hope and possibility in the team, which was heightened by our winning races. Getting close to races, Zenon, knowing he had worked us hard in the preceding months in preparation, would take it easy and let us recover mentally as well as physically.

As we would launch for our race he would often cheerily encourage us to enjoy the possible accomplishment of our arduous labor by wishing us to “hava fun!”

Thanks for all you did to give us great experiences and fun Zenon. You will be missed.

-Bruce Appleyard, Stroke 87 & 88 PAC-10 Championship Crews

Cincinnati Hosts the National Collegiate Rowing Championships

Established in 1982 the purpose of the “National Collegiate Rowing Championship,” aside from generating interest in rowing in the Midwest, was to create a national championship bringing together the IRA champion, the PAC-10 champion, the Eastern Sprints champion and the Harvard-Yale winner. During those years Harvard and Yale while attending the Eastern Sprints did not attend the IRA. It was not until 2003 that Harvard and Yale’s men’s varsity eight ended their long absence from the IRA. The travel to the regatta of those designated invitations was paid by the Cincinnati hosts. As an inducement the winner would receive an expense paid trip to the Henley Royal Regatta. In 1987 athletic directors of schools participating in the National Collegiate Rowing Championship voted to “make it a violation for teams to accept airline tickets from private groups, such as the Cincinnati Regatta Inc., for winning the title.” Matt Solinsky, “Top U.S. Rowers vie in Cincinnati Regatta”, Cincinnati Enquirer, June 11, 1989, 37. As a result, the funds passed through a public trust called the Navy Olympic Rowing Fund for a grant to reimburse the expenses for the trip to England.

Other crews were allowed and other events, including women’s events were added. The first added events were the women’s 8 and men’s lightweight 8 added in 1986. The regatta was the creation of local attorney, and former Brown oarsman, Bill Engeman. The East Fork of the Little Miami River had been dammed in 1978, creating a large reservoir outside of Cincinnati in East Fork State Park named for U.S. Representative William H. Harsha, and served as the venue.

The championship regatta began in 1982 and ran through 1996, ending in advance of the NCAA women’s championship beginning in 1997. Although the women’s championship was moving to a separate NCAA structure the men’s collegiate championship at Cincinnati also ended, along with associated high school races since local sponsorship could not support the regatta with the high school races alone. “Princeton coach Curtis Jordan said he also wants to [continue to] come back [to a National Championship]. ‘What we would like to see is this regatta rotate with the Eastern Sprints and IRA to avoid having to row three 2,000-meter races in four weeks as we did this year.’” Bob Queenan, “Cincinnati Eight is Second as Rowing Event’s Era Ends”, Cincinnati Post, Jun 10, 1996, 19. During ten of its fifteen year existence, the IRA champion did not become the National Collegiate champion.

UCLA earned there way to the National Collegiate for six consecutive years from 1987 through 1992, including all five years during when Zenon Babraj coached the UCLA varsity 1987 - 1991.

1987

An article in the Los Angeles Times pointed out that the UCLA rowing program provided no athletic scholarships and that the men’s and women’s programs were run on shoestring budgets with Babraj earning $30,000 as a full-time coach and women’s head coach Jean Reilly at a part-time salary of $7,000. Ray Ripton, “Bruin Crew is Strictly for Amateurs” Los Angeles Times, 4 Jun 1987, 263. Lee Miller became the freshman/novice coach, after coaching two years at Washington and one year at Orange Coast. Miller had attended both institutions as an undergraduate, including as the coxswain of the 1983 PAC-10 championship crew. He had recently coached the Orange Coast novice eight to a Pacific Coast championship in 1986. “Staff”, 1988 UCLA Men’s Crew recruiting brochure.

F.O.U.R. sought to expand participation, especially among lightweights and women that had rowed at UCLA. A new working relationship was developed with the UCLA Foundation for administrative support services and the Endowment Fund had been set up within the Foundation. Plans for the 1987 UCLA Crew Classic to invite Keio University from Tokyo, and Washington to race the lightweights with lightweight alumni sponsoring $2,000 for their air travel to Los Angeles. The Washington lightweight defeated their UCLA lightweight hosts by seven seconds. Mills College racing the women’s team and Orange Coast racing the junior varsity and freshman heavyweights. Equipment additions included a Norwegian ergometer donated by F.O.U.R. and a purchase of a Vespoli racing eight through a donation from Julian Wolf and sales of the oldest equipment in the boathouse.

The Varsity eight earned dual victories over USC and UC Irvine during the season and a loss to California after placing fourth in the San Diego Crew Classic ahead of Stanford and California. The UCLA Crew Classic featured the Bruins (6:34.8) defeating Oxford (6:42.27) and Keio (6:52.57). Though Keio jumped out at the start their lead did not last with UCLA keeping a steady pace and picked it up toward the end as Oxford made its final move. Oxford coach Dan Topolski said, “I was quite pleased with our row. I thought we really did quite well. But UCLA is really moving up [compared to the 1986 UCLA Crew]. We knew they would be hard to beat.” Tracy Dodds, “UCLA Crew Credits Coach for Win Over Oxford”, Los Angeles Times, 19 Apr 1987, 92. This followed Oxford’s March 28 victory over Cambridge following the Oxford mutiny that resulted in replacing several internationals in Oxford’s first crew.

UCLA won the Varsity eight at the Pacific Coast Championships with California second and Washington fourth. Going into the final 200 meters California was ahead of UCLA by six seats with Washington farther back. The Bear’s stroke caught a crab and allowed UCLA to finish eight seats in front. Washington’s coach Erickson stated that his Huskies “didn’t have the intensity required to win. UCLA just rose to the occasion.” UCLA’s stroke was Bruce Appleyard who had transferred from California, after two years and differences with California coach Hodges. Jim Rattle, “UCLA Makes Big Splash at Rowing Championships”, Sacramento Bee, 18 May 1987, 17. UCLA placed fourth in combined men’s/women’s points among the PAC-10 schools, including a second place finish in the Freshman/Novice four and fifth place in the Junior Varsity eight. Representing the Pacific Coast Championship made its first trip to the National Collegiate Championship where they finish fourth ahead of Dad Vail regatta champion Temple University.

University of Washington dropped men’s lightweight rowing in 1987, in part due to change in head coach from Dick Ericson to Bob Ernst and “because of Title IX, he needed to reduce the number of male rowers at UW.” David Arnold, Pull Hard! Finding Grit and Purpose on Cougar Crew, 1970-2020 (Washington State University Press: Pullman, WA, 2021), 174.

1988

UCLA suffered the graduation of four oarsmen from their 1987 championship crew, consisting of World Champion (#4 seat in the U.S.A. 1987 eight) Mike Still, stroke Bruce Appleyard, Chris Hirth and Richie Sax. It was hoped that several transfers from Orange Coast and a few other West Coast teams would help bolster the returning members of the team for continued success. Mike Still was a volunteer assistant coach during the season.

In June 1987 it was announced to the alumni that the annual amount need for the 1987/88 budget was $60,000, increasing from the $40,000 supplement to the $75,000 Athletic Department of 1986/87. Further the UCLA Crew Classic had added a $10,000 average annual expense. “Corporate sponsorship of the Classic has not been significant so the responsibility for this funding clearly lies in the hands of concerned individuals.” As the end of the annual campaign approached, on May 31 they had only raised $23,000. Terry Oftedal, “1987-88 Operations Budget Campaign”, Bruin Strokewatch, June 1987, 2. It was a challenge to fund raise to cover operating expenses, rather than accumulating funds in the endowment, and there was the dread that soon the program would need to be self-supporting without Athletic Department funding.

In January 1988 the USRowing Report announced that “the UCLA Crew program has been cancelled by the athletic department, effective June 1988.” (Volume 2, Number 2, 2.) The announcement encouraged Association members to send letters supporting the team to Athletic Director Peter Dalis. The program continued but the threat of cancellation and challenges of fund raising continued.

The varsity eight completed the season through the Pacific Coast Championships with only one loss, winning that for the second consecutive year. The San Diego Crew Classic final included excitement. As the Bruins “were passing Navy, the Midshipmen crossed into UCLA’s lane. The crews collided and drifted across the finish line with oars locked together. Navy was disqualified,” and UCLA became the Copley Cup winner. In the final, Navy had led the race “from the 250-meter mark on, infringed upon UCLA’s lane-one position twice early in the race without incident. Then, with 100 meters left, the second-place Bruins picked up their stroke count and began closing rapidly. With 40 meters remaining, they trailed by only three seats, and the Midshipmen began to angle toward them again. The boats collided with 15 meters left, locked oars and drifted to the finish in 6:07.50 – nearly two seconds ahead of Wisconsin.” Chris Clarey, “UCLA Victory a Classic as Navy Loses its Bearing”, San Diego Union, 3 April 1988, 170. UCLA had the momentum and was advancing on Navy as described by coxswain Jay Tint, “When they came into our lane, I said ‘Not again.’ And it happened, and the Cup’s ours. We’re taking it. No questions asked.” UCLA became only the fifth school, joining Harvard, Pennsylvania, Washington and Cal, to win the Copley Cup for varsity eights in the fifteen year history of the San Diego Crew Classic.

The Bruins raced to a seventeen second win over Cal on Ballona Creek. Their one loss was to Harvard at the Redwood Shores Classic but the Bruins defeated Brown and Pennsylvania. They also won at the Newport Regatta. Commenting following the Pacific Coast victory “There’s no secret,” said Zenon Babraj, UCLA’s second-year men’s coach. “If you’re winning all the races so far, you’re expected to win.” Matt Peters, “UCLA, Washington Prevail in Pacific Coast Rowing Finals”, Sacramento Bee, May 23, 1988, 2. As the Pacific Coast champion, again UCLA advanced to the National Collegiate Championship and finished in sixth place.

Other varsity performances at the Pacific Coast Championships included the Junior Varsity eight placing third and the varsity four second in the petite final. The Freshman eight enjoyed a very successful season with third place finishes at the San Diego Crew Classic and Newport Regatta, dual wins over Stanford and USC and an exciting come from behind two-seat victory over Cal, and second place at the Pacific Coast behind Washington. The Freshman eight attended the IRA and finished in sixth place in the final.

The Varsity eight set their sights on the top event in England’s prestigious Henley Royal Regatta. The Varsity eight lost to Syracuse (fourth place at IRA and sixth at a windy Eastern Sprints) by three lengths (Syracuse’s time was 6:45) in their first race in the quarter-final round of the Henley Royal Grand Challenge Cup. Both the Freshman trip to the IRA and the Varsity trip to England were privately funded by parents and oarsmen.

1989

In addition to head coach Zenon Babraj and freshman coach Lee Miller, Mike Still became a part-time assistant after serving as a volunteer coach the year before.

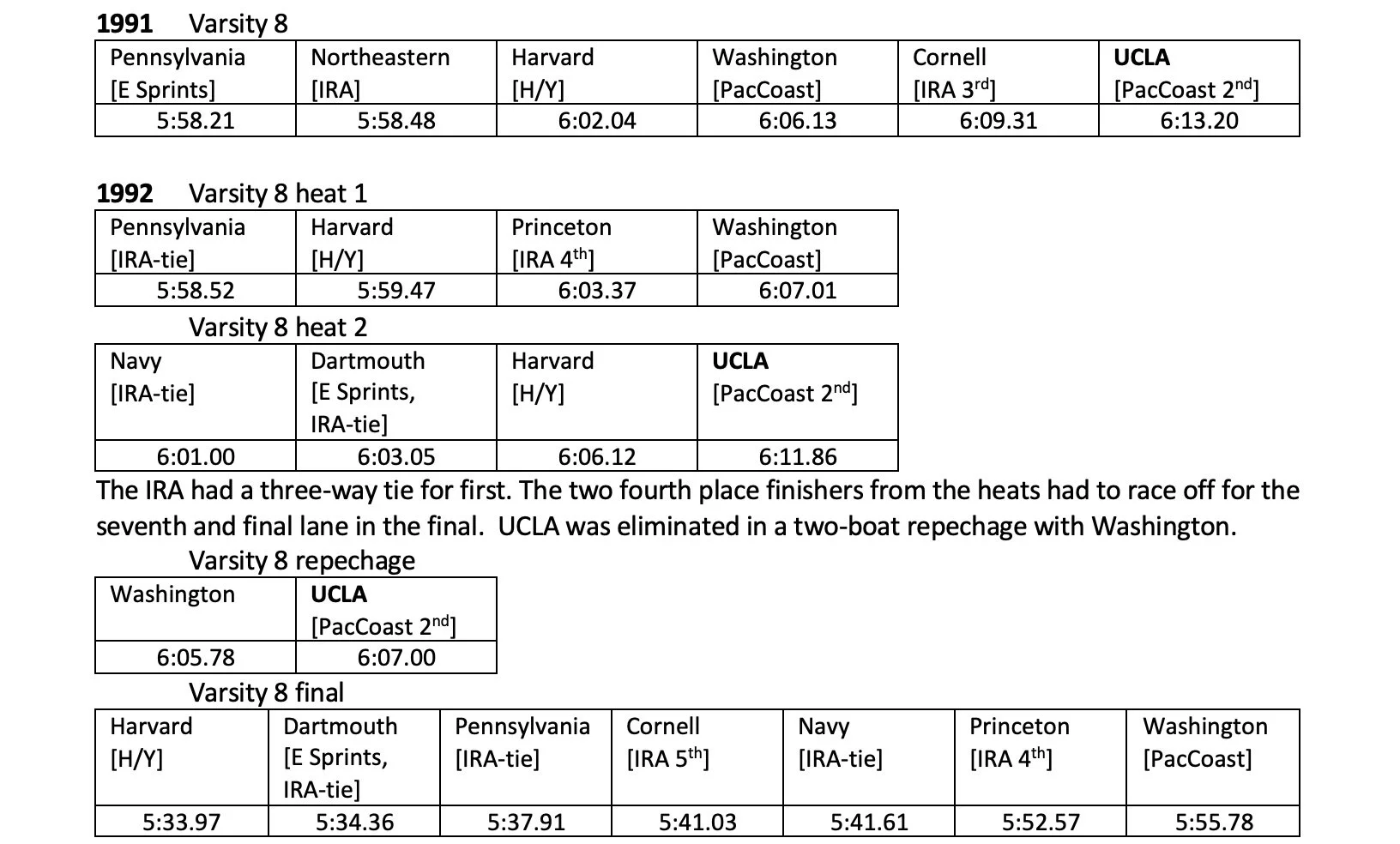

In the face of shrinking funding from the Athletic Department, the cost to keep run the program for the year, including maintaining the boathouse and equipment, a full-time rigger and men’s and women’s coaches was estimated by F.O.U.R. president Kevin Sherwood would be $244,000 Tina Fisher Forde, “A Warsaw Concerto”, Los Angeles Times, 12 Apr 1989, III-6. In addition to the increasing needs of the team the due to success and aging equipment, the Athletic Department was reducing their share of expenses from $75,000 to $35,000 with F.O.U.R. to fund the reminder, there was a lack of appreciation of the team’s success by the Athletic Department. Mr. and Mrs. Franklin Murphy donated $40,000 to F.O.U.R.

Tina Fisher Forde, “A Warsaw Concerto”, Los Angeles Times, 12 Apr 1989, III-6.

In the fall of 1988, for the first time UCLA traveled to Boston and placed fourth overall, and the third collegiate crew behind Harvard and Navy, in the Championship Eight at the Head of the Charles.

The spring season included a third consecutive Pacific Coast Championship in the varsity eight and a trip to the IRA for three UCLA crews. Zenon volunteered that the trip to Syracuse for the IRA was accidental and unplanned. It was made possible when nineteen members of the team each received $200 travel vouchers from an overbooked flight returning from Redwood Shores, to return to Los Angeles on a later flight. At the IRA the Varsity eight finished fourth, the Varsity pair-without-coxswain sixth and the Varsity four-with-coxswain second. Returning a third time also to the National collegiate Championship in Cincinnati the Bruins placed sixth. Zenon shared with the alumni that he was not satisfied with the performance, putting aside an excuse that the team was taking final exams at UCLA. He felt that the UCLA team was not comparable with the teams they raced in Cincinnati and even some of the teams they beat at the IRA. He shared challenges that the program faced.

After the Pacific Coast Championship victory while setting a Lake Natoma course record of 5:45.80, stroke Mike Farrell, who had been in all three championship boats, remarked “We did it for the J.V.” The UCLA Junior varsity had been considered the fastest on the coast during the season and had to withdraw from the race when several of its members came down with food poisoning. Scott Forest “Three in a Row”, UCLA Strokewatch (reprinted from the UCLA Daily Bruin), October 1989, 2. The season’s varsity squad was composed of only seventeen oarsmen and when three got sick at the Pacific Coast, UCLA was unable to race “our No. 1 ranked J.V. boat.” Zenon Babraj, “Straight Talk From Zenon”, UCLA Strokewatch, October 1989, 4.

Sacramento Bee, 15 May 1989, 27.

Both UCLA head coaches, Zenon Babraj and Kelly Salonites, were named PAC-10 coaches of the year. The pair-without-coxswain of Mike Still and Craig Webster had been coached by Zenon and won the trials to represent the USA at the World University Games, as the only American boat from a single university. Teo Bielefield (UCLA 1989 varsity eight #4) made the USA eight that raced at the World Championships and finished fourth.

Zenon Babraj, “Straight Talk From Zenon”, UCLA Strokewatch, October 1989, 4.

1990

Mike Still became the freshman coach as Lee Miller moved on to become the head coach at Loyola Marymount. There was excitement that that an Empacher racing shell had been purchased for the varsity. In an article highlighting the success of the UCLA women’s team under Kelly Salonites, assistant athletic director Judith Holland was quoted as saying, “We will continue with the core funding for rowing. It will not be [downgraded to] a club sport. It will not be discontinued. We will try to find ways to help. But our hands are tied.” Salonites said, “But small sports are suffering. Nobody wants to hear about rowing. But how many sports is it going to take to become extinct before people notice what’s going on at universities? The money is there,” she said. “They choose to put it somewhere else. It’s a policy decision. UCLA rowing is getting less than UC Davis and other California schools. We have developed the program to one of the best in the country.” The author cited that “of the $1.6 million designated for sports from student registration fees, the UCLA crew program receives $55,000 a year from the athletic department -- $25,000 of which is for the women. Four years ago, the figure was $150,000 for men alone. … The men’s allotment from the athletic department goes strictly to support the boathouse. Salonities is paid $12,000 from the women’s allotment and $8,500 from F.O.U.R. She raises the money to pay her freshman-novice coach Marisa Hurtado, $6,000 for travel, insurance, gas and supplies. … That the women pay their own expenses at regattas, buy their own uniforms and pay their own airfare.” UCLA’s women had won the Whittier Cup at the San Diego Crew Classic along with the junior varsity eight, then defeated Radcliffe and their only defeat had been to Princeton. One of the female athletes was quoted as saying, “They said if we won, things would change. Well, we’re winning and things are the same.” ”Tina Fisher Forde, “UCLA Women Row to Acclaim on a Shoestring”, Los Angeles Times, 15 May 1990, C-14. The Women won the Pacific Coast Championship and concluded their season at the Women’s National Championship in Wisconsin finishing fourth in the varsity eight and second in the junior varsity eight.

At the San Diego Crew Classic the varsity eight finished second to Harvard in a re-row of the Copley Cup. Wisconsin finished fourth the first time but protested they didn’t hear the start, but left the stakeboat anyway. Washington had won the first running of the final. UCLA’s freshmen won their final. Cal’s men won the Wallis Cup dual by 9.8 seconds on Ballona Creek, though Cal’s women lost to UCLA’s by 8.5 seconds.

Foregoing the Invitational event at Redwood Shores UCLA attended the inaugural Potomac International Regatta, the organizers sought to bring together the best collegiate crews from both coasts along with England’s Oxford and Cambridge. Oxford and Cambridge were winding down following their 4.5 mile annual Boat Race. UCLA won its semifinal over Princeton, Wisconsin-B and Virginia, and went on to finish second in the final to Harvard (5:35.44) ahead of Wisconsin and Princeton. The UCLA junior varsity and freshmen eights both finished second to Wisconsin in their finals.

In a dual with USC, the UCLA novice, instead of the freshman, defeated USC’s freshmen and UCLA junior varsity eight overcame the USC varsity. The Newport Regatta was the same weekend as the Cal-Stanford Big Row at which Stanford got the better of Cal. At Newport the Bruin varsity finished over 33 seconds ahead of second place UC Santa Barbara. The Junior varsity eight put up a good fight but finished in second behind Orange Coast, and the Bruin freshmen won the Connie Johnson Cup and had only one loss to Wisconsin at this point in the season.

The stage was set for a showdown at the Pacific Coast Championships. UCLA women’s team placed first in the varsity eight and junior varsity eight, and third in both the novice eight and novice four. The men’s team was second in the freshman eight and third in the junior varsity eight. The varsity finished second to Washington by 1.2 sec as Washington surged to the lead in the final 30 strokes, but ahead of Cal in third and Stanford in fourth.

For the fourth consecutive year UCLA’s varsity attended the National Collegiate Championship, Even after placing second to Washington at the Pacific Coast Championships they placed third, their highest finish with Washington in sixth place. Babraj said, “We are a young team and have everyone back from this year’s boat except for one rower [senior Stefanos Volianitis of Greece]. Next year we could be one of the favorites to win the national title.” “UCLA Roars to Third-Place Finish at National Championship”, Los Angeles Times, 21 June 1990, 514. Babraj was named the PAC-10 coach of the year for the third consecutive year and Salonites for the second.

1991

After four consecutive PAC-10 titles, a call to action appeared in the Summer 1990 UCLA Magazine with the support group F.O.U.R. “seeking to recruit new members willing to help keep UCLA crew alive and well and continuing in its winning tradition.” The article cited that over the previous three seasons F.O.U.R. had “funded 50 percent of the operating budget for the crew program, as well as provided support for post-season competitions.” This coming year that support was being increased to 80 percent as support from the Athletic Department diminished. F.O.U.R., with the help of Texaco USA, had launched a campaign to fund a $3.5 million endowment for the rowing program in 1989. Part of the benefit of that was to be two new shells, an eight, “Manny Gonzalez ‘74” and a pair oared shell, “D.K. Cable ’41.” “FOUR Seeks New Friends”, 74.

At the November alumni reunion, F.O.U.R. president Kerry Turner reported on the current financial responsibilities and that “F.O.U.R. must raise more than $200,000 per year to maintain the combined crews.” Adora Chan Gould, “Inaugural Reunion of UCLA Oarsmen”, Strokewatch, Winter 1991, 1. Although F.O.U.R. stated that it had successfully completed a five-year struggle to confirm the programs status under the Athletic Department, there was diminishing financial support from the Athletic Department and increasing program costs related to equipment, travel and coaching. The mission of F.O.U.R needed to change to organized fundraising rather than merely an alumni support group.

The varsity team roster consisted of 24 names, with three internationals (junior Leif Pettersson-Sweden, and freshmen Ristic-Yugoslavia and Throndsen-Norway), five from Orange Coast College and one from UC Irvine.

An announcement was made in March that the UCLA rowing program would be dropped from the athletic department at the end of the season, along with men’s water polo. Even after PAC-10 titles for three of the past four years, “cutting crew would save $214,000,” of a $3 million deficit. “The coaches have all been told their contracts won’t be renewed come July. The athletic department will not contribute the $55,000 to the $230,000 budget that it had been contributing. The crew athletes will no longer be able to pre-enroll or coordinate class schedules with crew schedules or use the university trainers.” Other varsity teams were naturally nervous that it could happen to them, including Wisconsin who had placed a budget cap of around $180,000 placed on their program. Kevin Sauer, coach of the up-and-coming Virginia program, being run with rowers doing chores and fund raising, noted his surprise that a university would go after its crew program. “Crew seems to me to be what college athletics is all about,” said Sauer. “You can have people coming to the university do this without any experience. They don’t have to be able to hit [a] 20-foot jumper or dribble behind his back. Lots of people can pick up this sport. Its’s a sport for the masses.” At Wisconsin the amount spent per athlete was rather low for a rower, an average reported as only $400, compared to “$45,000 a year on each football player, $30,000 on each women’s basketball player, $17,000 on each tennis player.” Diane Pucin, “Will Cuts Ground the Crews?”, Philadelphia Inquirer, 10 May 1991, 57.

In one report the UCLA athletic department was cited as agreeing to contribute $55,000 annually, which was about 20% of the total program cost five years ago, with boosters to provide the rest. Reporter Jim Murray cited Athletic Director Dalis as stating that “’the boosters failed to meet their quota Crew cost the school about [a total over five years of] $375,000, or about $75,000 a year.’ Murray opined, “they used to say that football built character, although we don’t hear that much anymore. But rowing actually did.” Even actor Gregory Peck publicly called for the support of UCLA rowing. He had rowed for Cal in 1937-38. Peck said of his rowing experience, “it’s the most grueling sport know in college. … We never got anything out of it but love of competition and camaraderie and the feeling of having exercised the mind and body in a wholesome exhilarating way.” Peck further praised rowing, “I think it’s prestigious for the university, even though it does not attract 90,000 people.” Jim Murray, “Big Voice Speaks Out for Crew”, Los Angeles Times, 28 April 1991, C-1, C-4.

One of several letters to the editor that appeared in the Los Angeles Times was by past assistant coach Mike Bennett. “Wrestling, water polo, crew, it is just the beginning,” warned Bennett and if there was not an outcry from alumni about what he termed the mismanagement of the athletic department, “football and basketball are going to be the only games left at UCLA.” Los Angeles Times, 16 May 1991, 237.

UCLA’s men placed fourth in the Copley Cup at the San Diego Crew Classic and second in the women’s Whittier Cup behind Boston University. Cal Coach Bruce Beall credited the Bruins, “they are very impressive” since in the final the Bruins were at 34 strokes per minute with all the crews striking at 36 or 37. Jim Bainbridge, “Cal Needs More Speed Against UCLA”, Oakland Tribune, 11 April 1991, 36. UCLA defeated Cal by one length, about four seconds, in their dual for the Ben Wallis Cup, while Cal’s junior varsity, freshman and novice eights scored decisive victories. The Bears got closer than in San Diego and shuffled their lineup but couldn’t settle from a stroke rate of 37 ½ to 34 ½.

In their first appearance the UCLA women won the wind swept second annual Potomac International Regatta defeating Wisconsin, Northeastern and Virginia in the final. The UCLA men with the men’s eight finishing fifth finishing first in the petite final ahead of Georgetown, Cambridge and Wisconsin. The men’s final was won by Harvard one length ahead of Brown, followed by Northeastern and Princeton.

The Bruins were again successful at the Newport Regatta with the varsity eight placing first, the junior varsity second and the freshman eight third. At the Pacific Coast Championship, the women’s varsity and junior varsity eights champions and the novice eight finishing in second place. The men’s varsity eight led the way on the men’s side with a second place finish to Washington, fourth place in the novice eight and fifth place in both the junior varsity and freshman eights. Babraj was not sure if the varsity wanted to race in Cincinnati, since it would be their last race as a varsity and with him as their coach. For the fifth consecutive year UCLA’s varsity attended the National Collegiate Championship, their final race as a varsity team, and placed sixth. In their only appearance in the parallel Women’s varsity eight at Cincinnati UCLA finished in third place

When the axe fell for both women’s and men’s crew, eliminating them from the UCLA Athletic Department, they were not the only team being dropped. Men’s water polo was also to be discontinued, however they were saved “by the fast work of the Water Polo Alumni Group, which raised more than $100,000 in just six weeks.” They had been a three-time national champion. In the story from the UCLA Magazine, Wendy Soderburg, “Still Afloat”, Fall 1991, 52. a small committee “just called people on the phone and asked them to give.” They generated enough to generate $25,000 annually to cover the team’s operating expenses over a five-year period consisting of paying a part-time coach, officials’ fees, entry fees and travel to compete at Cal and Stanford. Speedo served as a corporate sponsor donating water pool equipment and uniforms. The deal was if at the end of the five-year period, the alumni group raised enough to endow the team permanently, it would go back to being a fully supported sport. The men’s water polo team continues as a varsity sport at UCLA. In 1991 senior associate athletic director Judith Holland cited the dropping of varsity sports as a trend as funding for intercollegiate athletics has “gone a little sour.” However, she believed that the UCLA athletic program was now stable.

The rowing teams at UCLA were not as fortunate, even with F.O.U.R. working to raise money, they became club teams after the 1991 season under the auspices of Cultural and Recreational Affairs. It would mean significant changes in the program, at least until the women’s rowing program was restored to varsity status a decade later. On February 8, 2001 it was announced that the UCLA women’s rowing team would regain varsity status for the 2001/02 academic year and be fully operational for the 2002/03 school year to meet Title IX compliance, while the men’s team would remain under the Club Sports Program in the UCLA Recreation Department.