Female Coxswains of Men’s Varsity Crews

An oddity, to being banned, then approved, to accepted practice.

Female Coxswains

|

Female Coxswains |

In the 1934 motion picture Student Tour staring Jimmy Durante, the female lead steps in to replace the ailing coxswain of fictional Bartlett College in their climatic race in England. She had difficulty steering but ended up singing the college fight song to motivate her male crew to victory. I had female coxswains from the time I began rowing at UCLA in 1974, so I never thought of it as a big deal. In fact, other women had mightily labored before them.

In the years from 1943 through 1946 there was limited collegiate rowing as most programs shut down. Following WW II, athletics were in the process of restarting at many colleges, including at crew at UCLA. In 1947, the role of women supporting the men’s rowing team was very different. UCLA freshman Joan Hudson was selected as queen of Crew Week by members of the Bruin Rowing club to preside over the race against San Diego State and the Crew Dance.

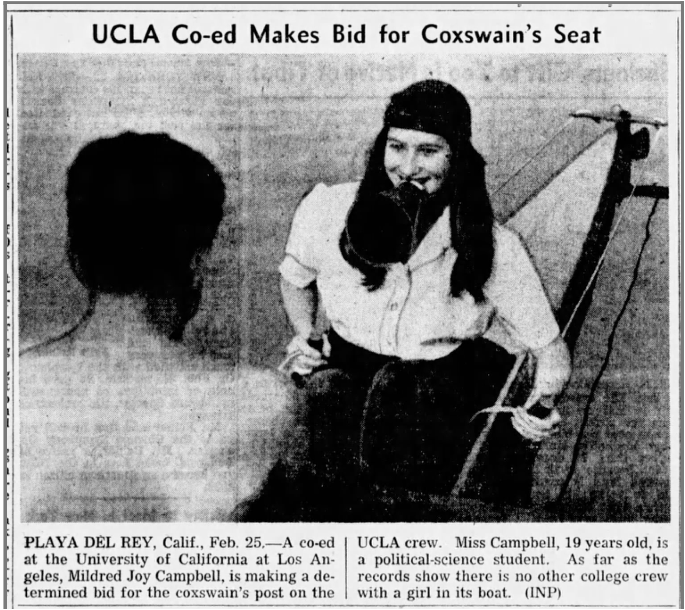

Buffalo (NY) Evening News, 25 Feb 1948, 37.

By Frank Neil-International News Service,

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, 23 Feb 1948, 16.

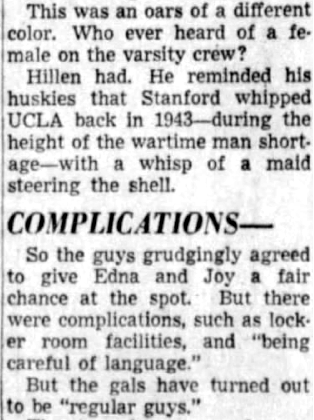

During February of 1948, Mildred Joy Campbell made news across the country and was discussed in a syndicated men’s outdoors columns with several different titles, as she made a bid to become a coxswain on the UCLA men’s crew. She and her roommate Edna Saxton reported to the call out that spring along with 78 male crew aspirants. News articles stated that the rowers were “leery at first” to give the women a try, but were allowed by UCLA’s coach Bob Hillen.

At least in news photos, Mildred Campbell was shown actually coxing a shell, often with a header above the photo as “Barking Beauty.” Mildred graduated in 1949 and her yearbook caption did not include mention of the crew, however it was mentioned in Edna’s 2008 obituary. A month prior to the first race of the 1948 season both young women were released from the team after an anonymous poison pen letter was sent to coach Hillen and the athletic director claiming that the presence of the two female coxswains was a “detriment to the prestige of the male sex.” UCLA Daily Bruin Reporter Joe Bleeden wrote that the letter went on to say that men were degraded during the last war by having to train under women, and that seemed a shame to have the he-men on the team commanded by girls now. Joe Bleeden, “Girl Coxswains Canned; Hillen Seeks Replacements”, UCLA Daily Bruin, 2 Apr 1948, 6. There was support for the two young women through a letter to the editor. John Johnson, “For Girls and Victories”, UCLA Daily Bruin, 6 Apr 1948, 7.

Decatur (IL) Herald, 2 May 1948, 19.

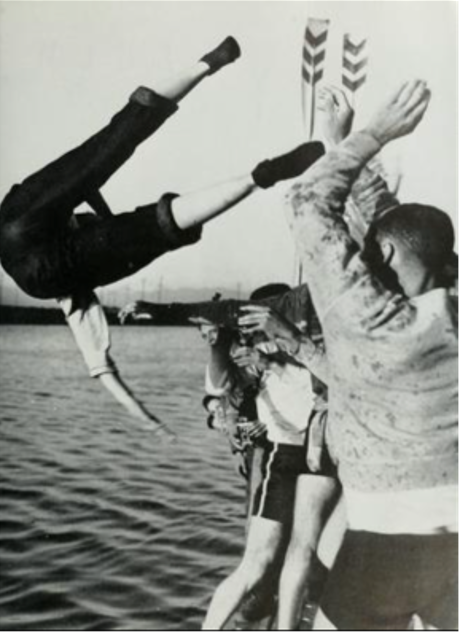

An image of Edna Saxton appeared in several newspapers and in the Southern Campus yearbook, however her image was of her backside as she was airborne. Often printed with a header of “Oops-a-Daisy” and a caption “Girl coxswain Edna Saxton (in air) is tossed into a Los Angeles, Cal., creek by University of California at Los Angeles crew members rehearsing the traditional dunking. Edna is one of UCLA’s two girl coxswains, both were chosen for the job because of their light weight.” “Oops-a-Daisy!”, Santa Cruz (CA) Sentinel, 14 Apr 1948, 5.

Redding Record-Searchlight and the Courier Free Press (Redding, CA) Apr 19, 1943, page 4.

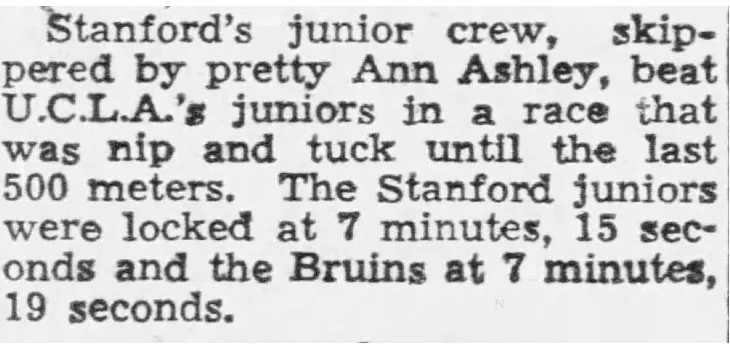

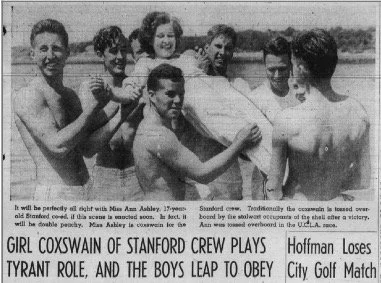

In fact, it was Stanford’s junior eight in April of 1943 that had defeated UCLA’s junior crew on Ballona Creek that had raced using a female coxswain.

In an article preceding their race with UCLA, Ann Ashley was listed as the coxswain of Stanford’s third shell. She is cited to have raced twice that season, first defeating UCLA’s junior crew then losing to California. She was cited as the “first girl coxswain in the history of collegiate crew racing in U.S.A.” In the California race her racing attire was “white slacks and a well-fitted red and white striped jersey,” The closing paragraph of the article read “Crew in these parts have been strictly a participant sport. Ann is transforming it into a spectator sport as well.” “Girl Coxswain Barks Orders to Oarsmen – Ann Ashley Uses Power Play”, Montreal Daily Star (Montreal, Quebec, Canada), 11 May 1943, 23.

Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California), May 10, 1943, page 15.

The instances of females serving as coxswains for men’s crews in the 1940s and even in the 1970s were painted as novel and the young women described as pretty or cute and considered for their light weight and motivational abilities. Earlier inclusion by female coxswains of men’s crews were usually at smaller colleges (Santa Clara University, UC Irvine) or club-level teams (University of Oregon, Stanford University).

Coach Duval Hecht claimed that the first women to be coxswains on the West Coast were at UC Irvine in the fall of 1966 where he had founded the rowing program in the fall of 1965. “Later, he said, the Western Intercollegiate Crew Coaches Assn. outlawed women coxswains but two years ago [1973] the coaches rescinded the ban.” Ray Ripton, “Coxswains Have Spirit, Sensitivity – Women Pull Weight With UCLA Crew”, Los Angeles Times, 1 Apr 1976, 151. In addition to being under the 120 pound minimum weight for coxswains, Hecht cited that the young women were “very good with the psychological aspects of crew.” At the 1967 Western Sprints Karen Shoemaker, after having become a coxswain the previous October when she tagged along with her rower boyfriend when Hecht ran short of male coxswain candidates, raced in UC Irvine’s junior varsity crew, placing fifth. She also talked a friend, Barbara Slotten, into coxing one of the four-oared shells. Jim McCormack, “Irvine’s Girl Coxswain – Down to the Sea in . . Slips?”, Independent Press-Telegram (Long Beach, California), 21 May 1967, 49. Neither were mentioned in subsequent newspaper articles.

The Western Intercollegiate Crew Coaches Association had adopted a rule prohibiting females in male competition on August 26, 1967 after UC Irvine showed up with female coxswain Shoemaker. Oregon State coach Karl Drlica recounted that because she “got the race all fouled up… The men got mad and the coaches said no more girls.” “You Are Needed – Girls: Row, Row, Row Your Boat”, Albany Democrat-Herald, 27 Apr 1973, 14. The WICCA included twenty-three colleges, including all the Pac-8 Conference schools. In 1972 the University of Oregon, a club-level team, placed a female coxswain in their shell, Victoria Brown. Oregon State University coach Karl Drlica was the president of the Association and refused to race against the University of Oregon club crew with coxswain Victoria Brown in April 1972. Brown had coxed her varsity men’s crew to a victory over Seattle University, the prior weekend. The Oregon crew, including Brown, voted to replace their coxswain with a male to host the upcoming race with Stanford and Oregon State. The University of Washington also refused to race Oregon with Brown as coxswain. Oregon State later offered to race Oregon with Brown as coxswain in an unofficial race where the losers would buy steak dinners for the winners. Oregon did not accept. Drlica stated that, “from a team standpoint mixed crews are impractical because they open up potential emotional conflicts among crew members and because, on trips, they require extra funds for lodging.” Roy Gault, “OSU Crew Refuses to Row Against UO Girl Coxswain”, Corvallis Gazette-Times, 29 Mar 1972, 15. University of Oregon law professor and faculty representative of the Pac-8 Conference, Wendell Basye, countered that “there is nothing in the Pac-8 regulations that says a female can’t compete.” Basye was also unable to find a supposed NCAA rule that also banned females from coxing male crews, especially since rowing was not governed by the NCAA. Basye further said “it’s up to the institutions prerogative whether or not it allows females to compete.” “Vicky Takes Step For Women’s Lib, Serves as U. of Oregon’s Coxswain”, Daily News-Post (Monrovia, California), 1 Mar 1972, 20. While Victoria Brown did not continue coxing for Oregon after the 1972 season, her impact was felt. The controversy ran in newspapers across the country and was the subject of an article in Sports Illustrated entitled “Case of the Ineligible Bachelorette”. Kenny Moore, “Case of the Ineligible Bachelorette”, Sports Illustrated, 17 Apr 1972, 82, 84-85. The ruling by the WICCA changed in January 1973. The 1973 Stanford men’s team had three female coxswains (Dawn Carper, Nancy Ditz and Sherrie Anderson) “Coeds Assist Card Crew”, Palo Alto Times, 25 May 1973, 36. add there were others at Western Washington and the University of British Columbia. Drlica placed his first female coxswain (Carol Schmidt) in his junior varsity shell in 1973. In 1978, Katherine Casey alternated with a male as Oregon State’s varsity coxswain. Additionally, Barbara Bosch became the men’s varsity coxswain in 1979. Roy Gault, “Drlica Changes With the Rules”, Corvallis Gazette-Times, 27 Apr1979, 17. Even after the restriction was lifted, Drlica still warned of the potential that “a couple of guys get a little more interested in her than just as a teammate … they may start dating her and potential jealousies and so on can emerge. Then you’ve really got troubles.” “You Are Needed – Girls: Row, Row, Row Your Boat”, Albany Democrat-Herald, April 27, 1973, 14. One of the first female coxswains at the 1973 Western Sprints was Santa Clara’s Ann Clarkin in their freshman eight.“ Washington Favored in Crew Race”, San Francisco Examiner, 17 May 1973, 54.

There were still more hurdles to overcome, but the way was clear on the West Coast. The next coxswain to make news was Mimi Sherman of Santa Clara University. There were four female coxswains and only one male and on Santa Clara’s men’s crew in 1973. The women were all freshmen. Mimi Sherman raced as the coxswain of Santa Clara’s freshmen four at the 1973 IRA regatta. She is acclaimed to be the first female coxswain to race at the then all-male IRA regatta. Santa Clara had placed sixth at the Western Sprints in the freshmen eight, won the pair without-coxswain, and placed third in the varsity four final. Mimi Sherman’s Santa Clara crew finished fifth in the grand final, ahead of UCLA who was sixth. Also at the 1973 IRA UCLA was the varsity four champion and Santa Clara placed second in the pair-without-coxswain. Santa Clara did not attend the IRA regatta during 1974, 1975 nor 1976. At the 1974 Western Sprints, Santa Clara’s best showing was a fourth place finish in the lightweight eight, and third and fifth in the lightweight four. In 1974, she had come to Henley Royal but was refused the opportunity to compete. Although there was not a specific rule preventing a female coxswain, the regatta stewards declared that “It would be against the traditions of Henley.” Noel Hughes, “Henley Regatta Bans Girl”, Lansing State Journal (Lansing, Michigan), 1 Jul1974, 27. Although she had been informed prior to leaving the U.S. of the decision, she had come hoping that it might change and would be allowed to compete at the Nottingham regatta in advance of Henley. In the end, a male coxswain from Dartmouth was substituted and the Santa Clara eight was eliminated in the second round of the Thames Challenge Cup. In December 1974, the Henley Stewards announced that rule would be changed for the 1975 regatta, perhaps due to Sherman. After winning at the Nottingham Regatta, Mimi Sherman was permitted to race as the coxswain of her 1976 Santa Clara entry among the thirty-two entries in the Ladies Challenge Plate. Ultimately, they lost their first round by one length. That season Santa Clara had been plagued by low water levels on its home water on Lexington Reservoir. They had placed third in the lightweight eight at the San Diego Crew Classic and did not race as scheduled in the Cal Cup. The only Santa Clara men’s crews racing in the finals of the 1976 Western Sprints placed third in the lightweight eight and fourth in the open four.

Devin Mahony, in her book The Challenge, related her success as a female coxing men’s crews at Harvard [1983: undefeated freshmen eight and Ladies Challenge Plate winners; 1985: varsity eight coxswain and Grand Challenge champion]. However, Devin Mahony had begun coxing men’s crews while in high school at Phillips Academy, Andover.

On the West Coast, these earlier coxswains came to the sport without prior experience. Twenty-eight years after Mildred Joy Campbell and Edna Saxton attempted of to earn a seat in a men’s varsity shell at UCLA, female coxswains earned varsity letters as part of UCLA’s men’s crew. The first were my classmates that began in the fall of 1974, Shelia Parker [‘76, ‘77, ‘78] and Monica Smith [‘76]. Although the UCLA varsity women’s program had begun the year before Sheila and Monica matriculated at UCLA, neither the varsity women nor the female men’s coxswains had a locker room at the UCLA boathouse. Freshman Debbie Amstetter had coxswained UCLA men’s crews in 1973. Bill Hewitt, “Oarsman A Special Kind of Guy – Crew Racing Gaining Momentum in West”, Los Angeles Times, 22 May 1973, 39. An article in the May 10, 1976 Daily Bruin listed seven coxswains for the men’s team, six were female (In addition to Smith and Parker, Dennis Murrin, Gail Turner, Erin Mourey, and Patti Conrad. Steve Oates was the only male coxswain.) and two female coxswains (Sue Coon and Kim Palchikoff) for the women’s team. The article omitted two other female coxswains that were part of the UCLA men’s lightweight team (Jenny Williams and Tania Horton).

Perhaps the last barrier restricting coxswains to be the same gender as their crews was the international governing body of rowing. In early 2017 FISA amended their rules to read: “The gender of the coxswain shall be open so that a men’s crew may be coxed by a woman and a women’s crew by a man.” Rule 21, World Rowing Rule Book, 2021 edition including 2022 updates, 103. Along with a single minimum coxswain weight of 55.0 kgs. (121 pounds) regardless of the gender of their crews. After that change, Sam Bosworth became the first man to steer a women’s crew to international gold in the New Zealand women’s eight at the 2017 World Rowing Cup II in Poznan. In 2018, the Australians selected female cox Kendall Brodie to coxswain their heavyweight men’s eight while James Rook served as the coxswain of the Australian women’s eight. Rook had raced in Australia’s men’s eight and earned a silver medal in the men’s pair-with-coxswain at the 2017 World Championships. In 2018 Rook moved to the coxswain seat of the women’s eight where his crew earned a World Cup bronze, won the Henley Royal Remenham Challenge Cup, and placed third in the 2018 World Championships. He successfully coxswained Australia’s women’s eight during 2019 earning two more World Cup medals and the silver medal at the World Championship. Of the fourteen events in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, equally divided between men’s and women’s, only the eight-oared crews included coxswains. Each of those two events included seven entrants. In the men’s eight Eline Berger coxswained Netherland’s (fifth) eight becoming the first women to coxswain a men’s crew at the Olympics. Among the women’s eights Caleb Shepherd coxswained New Zealand (second) and James Rook coxswained Australia (fifth).

Certainly, the culture in America has changed from what it was in the 1940s and 1970s, and continues to change through to today. The acceptance of females doing jobs that were formerly restricted to males has changed. The athletic expectations by women and by men of the athletic performance of women has also greatly changed since the 1970s. In most of the stories of the earlier female coxswains their male rowers accepted them as part of the team. The novelty of a female coxing a men’s crew is gone. - Guy Weaser, UCLA ‘78